Checking in with Artist Sliman Mansour

- CARAVAN Arts

- Jan 21, 2021

- 4 min read

Updated: Dec 29, 2023

Could you share with us a little about your background?

I was born in 1947 in Birzeit (which means "well of olive oil"), a small town north of Ramallah. There are thousands of olive trees in and around Birzeit, and it is this landscape that I grew up and spent the summer playing and swimming in natural pools, and eating from all kinds of fruit that grows on the various fruit trees that are between the olive trees.

My father died when I was four years old and my mother put me and my brothers and sisters in a boarding school for orphans funded by German Churches. It was in this school, through a German house-father who was an artist, that I developed my artistic talent. Soon, everybody in my school saw me as the artist of the school, and even of my town, Birzeit.

Besides teaching me art, this teacher organized camping trips to many places in Palestine which broadened my understanding of my country and my love for it. After I finished school, I worked for a year or so to make some money to travel to the US to study art there. But then the 1967 war happened, and all my plans changed. I discovered an art college in West Jerusalem called Bezalel and studied there for three years, but was not able to continue because of money and other challenges. So, I left the college and started making art. Soon, I met several artists and within a short time we established an artist league, and started holding exhibitions in the main Palestinian cities. Our artwork was enthusiastically welcomed by the people. The military occupation also noticed our activities and started confiscating our posters and even some of the original artwork, and also interrogated artists - sometimes putting them in prison for periods of time. I was one of several artists who was imprisoned. They also censored our exhibitions. They even forbade Palestinian artists to paint in red, green, black and white, the colors of the Palestinian flag. During the first Intifada, Palestinians boycotted Israeli goods. Several artists, including me, boycotted art materials like oils and acrylics, and we started using natural materials and objects, making our own colors and dyes. I started using mainly mud, and other artists used leather and henna, and wood and other materials. These artistic experiments helped to change and develop Palestinian art, and it formed a link between traditional art (art done between 1950-1988) and the new contemporary art, which started to be created by young artists at the beginning of the 21st century.

What are the issues and topics that most concern you at the moment that you are expressing through your art? And how has your work been affected by the pandemic and other events in your region during the last nine months?

The issues are still the same ones that have existed since 1948. Nothing has changed - the occupation is going on. But some issues are more disturbing like land confiscation, prisons and torture, Jerusalem, the partition wall and Palestinian identity. For me I have started to feel old, and this became an extra issue in my art, especially during the pandemic. The pandemic forced artists to stay in their studios and so their production wasn't affected. But of course, loneliness has been felt by many of the artists, and the fear of the unknown danger affected the self-confidence of people in general.

Can you tell us a bit about what you’re working on at the moment and what your inspiration was?

Right now I am making a painting about the wall that surrounds Bethlehem, and my inspiration was the Christmas festivals. However, this year it was an especially sad Christmas season, as the main gate to the wall that leads to Bethlehem was closed, and Bethlehem became an imprisoned town.

How do you think the world will change as a result of Covid-19?

I think the moment people get the vaccine, everything will go back to pre-pandemic habits and practices. Even now, it seems people are almost acting as usual, albeit with a mask on their faces.

What are the lessons that need to be learned and behaviors that need to change as you reflect on our world at this time?

I guess people should try harder to create ties that bind their families together, because in the end, only families and friends can embrace the weak and lonely created by the pandemic. Also, countries should learn to respect and cooperate more closely with each other, because it has again been shown that being selfish is dangerous to the health of our world.

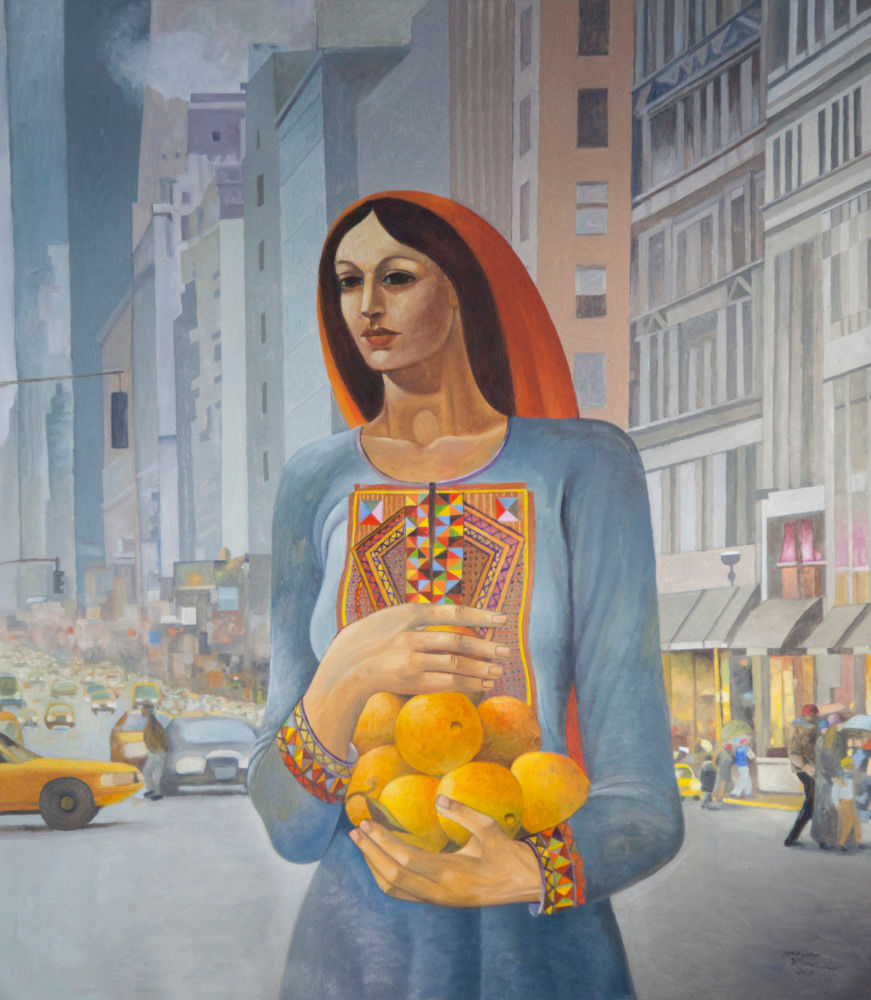

Born in 1947, Birzeit, Palestine, Sliman Mansour studied fine art at the Bezalel Art Academy in Jerusalem for three years. Sliman has tailored his comprehensive portfolio around the Palestinian struggle, portraying peasants and women in traditional dress in his early work. During the first Intifada against Israeli occupation (1987 – 1993), Sliman and other artists in the “New Vision” art movement started to boycott Israeli art supplies and using local materials like mud, leather, wood, found objects and natural dyes and colors in their work. Sliman was absorbed during the first years of his career with Palestinian identity, drawing inspiration from ancient cultures in the area, Islamic art (mainly calligraphy), folk culture and the Palestinian landscape. His recent work is centered on the individual figure to convey the different states of exhausting anticipation or loss, resulting from his experience of living under the occupation.

Sliman is a founding member of the League of Palestinian Artists and was its head from 1986-1990. In 1994, he co-founded the Al-Wasiti Art Center in East Jerusalem and served as its director from 1994 until 2003. He is also one of the founding members of the International Academy of Art in Palestine. He has held solo exhibitions in Ramallah, Sharjah, Cairo, East Jerusalem, Gaza and Stockholm. His group exhibitions include Museum of Oriental Art, Moscow, 1980, New Visions, Jordan National Gallery, Amman, 1991, Institue du Monde Arabe, Paris, 1996; Made in Palestine, Station Museum of Contemporary Art, Houston, Texas, 2003; He received the Palestine Prize for the Visual Arts in 1998 and the grand prize in the Cairo Biennial in 1998 and the 2019 edition of UNESCO-Sharjah Prize for Arab culture. He is a co-author of “Catalog of the Art of Palestinian Embroidery” (1986) and “Palestinian folk costumes” (1985). He currently lives in Jerusalem and works in Ramallah.

The opinions and views expressed by artists are those of the artists, and do not necessarily purport to reflect the exact opinions or views of CARAVAN.

Comentarios